Persevering Winter:

The Forgotten Symphony of the North

How Hunza’s timeless building techniques are redefining resilience

by Areeba Shuja

Once the backbone of Hunza’s built heritage, Cator and Cribbage – an indigenous construction technique constituted of stone and wood - has long since been dismantled in preference for the brittle promises of contemporary concrete and glass. Mirroring a rupture in time and values, natural morphology proves misaligned with ecological wisdom and resigned to its capital inclination. However, this article frames this catastrophe as an opportunity for exploration, reimagining disaster as a means for cultural reclamation. Centering Hunzakuts – the people of Hunza – as the ‘resilient’ protagonists, this project interrogates how the symbiosis between man and nature can be reintroduced through indigenous tectonics. Here, Cator and Cribbage techniques represent an act of resistance against the homogenizing effects of pro-capitalist development, providing material, community and climate resilience. Ultimately, the proposal aims to mend fractured landscapes, transforming vulnerability into agency.

[Image 1] Right above: Proposal rooted in the context.

Image by the author (2024).

[Image 2] Map highlighting the site in Shishkat (beige) and its association with the Attabad Lake (blue), site mostly populated with trees (teal) and farmland (green).

Image by the author (2025).

[Image 3] Timeline of the Attabad Lake Incident. The formation of the lake, depletion in landmass, and variation in water levels over time are noted.

Images attributed to Google Earth (2023).

[Image 4]

a. Diagram showing Cator and Cribbage construction detail

i. Wood interlacing

ii. Corner column detail

iii. Rubble infill

iv. Wooden beams

v. Sheathing

vi. Ha pattern functioning as a skylight

b. Exploded version

Images by the author (2024).

[Image 5] Hunza’s concrete developments, Ayza Shuja (2024), photograph, courtesy of the photographer.

[Image 6] Altit Fort Cator and Cribbage construction.

Image by Ayza Shuja (2024), courtesy of the photographer.

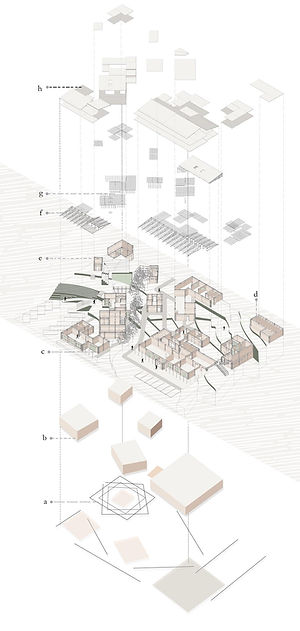

[Image 7] Exploration through the design proposal

a. Ha pattern

b. Use in design

c. South facing verandahs

d. Outdoor shelter spaces at the highest contour

e. Cator and Cribbage wall details

f. Mono truss roof system

g. Ha skylight system

h. Wood sheathing and further insulation against cold climate

Image by the author (2024).

[Image 8] Interaction between tourists and the natives.

Image by the author (2025).

INTRODUCTION: THE WEIGHT OF WINTER

Nestled deep within the Karakoram’s soaring peaks, situated at the helm of the meandering Hunza River, a striking yet haunting monument to calamity persists – the seemingly tranquil waters of the Attabad Lake. They mask not just physical ruin, but the extraordinary fortitude of a community that once mirrored its terra firma but now wrestles with its wrath. The drowned villages of ‘Attabad Payeen’, ‘Attabad Bala’, ‘Sarat’, and ‘Ayeenabad’ linger as reminders of the landslide of January 2010. Their presence marked only by the occasional skeletal treetop breaching the water’s glassy plane [1]. Occurring unrelentingly over the next six months, the consequential flooding built onto the possibility of impending repercussions as it inched towards surrounding villages [2].

A stunning super imposition of rugged mountainscapes paired with emerald valleys and the occasional snowcapped peak, Hunza’s postcard perfection knows no bounds. However underneath, this entity is no stranger to the devastating effects and consequences of natural turbulence. Forced to tolerate the repercussions of the First World - climate change, that great amplifier of inequity - looms here. Hunza’s valleys know too well the sudden violence of flash floods - torrents that materialize unexpectedly, hampering all affairs.

That night of January 4th in 2010 flaunted such indifference in the form of a devastating landslide, yet the locals responded in step. A response almost perfected from their practiced dance with destiny. They salvaged wooden beams and door frames from dismantled homes, uprooted fruit trees before the waters could claim them, and carried their lives uphill - piece by piece - in a defiant act of foresight [3]. Elegantly put, the educated inhabitants of Hunza unflinchingly described two facets of the disaster: first, nature’s indiscriminate fury, then the government’s failure to mitigate its aftermath. Therefore, the incident was shrouded with grievances but had no idealized outcome.

A shifting socioeconomic landscape, the unwavering resolve of the locals and their enduring heritage trace the trajectory of this article. Each catastrophic tremor not only shattered homes but eroded the very foundations of self-sufficiency. These relentless oscillations between destruction and fleeting recovery rewrote the social contract of the valley: Where once subsistence farming and communal trade thrived, now the gilded engine of tourism churns - transforming trauma into spectacle.

The resultant narrative follows the vibrant village of Shishkat in Hunza and its occupants who have had their identity intertwined with that of the lake, due to losing a third of their village to the landslide. The choice of a few to revive Cator and Cribbage techniques - indigenous methods of timber and stone craft forgotten in the wake of modernity - represents more than architectural preference. It is an act of cultural perseverance, a deliberate stitching of their identity back into the fabric of this wounded landscape.

Accordingly, this article culminates in a proposal that follows the lead of this homebound intellectual movement. These ancient tectonics of building whisper of a time when human hands worked with the earth, not against it, reawakening the

possibility of a symbiosis long buried beneath the march of profit and neglect. The goal is not to “save” Hunza but to support the Hunzakuts in saving themselves, on their terms.

THE ECHOES OF THE INDIGENOUS

This poses the question, what transforms a community into a beacon of resilience? Science may measure endurance, but Hunza’s magic lies in its very air - where fresh mountain winds sculpt both robust bodies and unbreakable spirits. Nestled in the Karakoram’s embrace, commonality is denoted by shepherds dancing along steep cliffs to reach alpine pastures, children laughing while carrying schoolbags up such inclinations, and elders outpacing visitors half their age.

The valley thrums with beautiful contradictions. Here, the Burushaski language - a linguistic enigma with no known relatives - mingles with Wakhi’s Persian-inflected melodies, both preserved through Urdu as a lingua franca. This cultural tapestry is matched by staggering 90% literacy rates, a testament to Ismaili values and the Aga Khan Development Network’s educational investments. Hunza’s lesson resonates clearly: true resilience isn’t just surviving hardship, but thriving through culture, intellect, and community. The mountains may have made them strong, but their choices made them extraordinary.

The architecture of these mountains is born of necessity, each article carefully considered and articulated. Stone dominates these constructions, attributed to the land generosity: an endless supply of rugged slabs, patiently waiting in the hillsides to be shaped into shelters. Timber, due to being scarcer here than in the greener Himalayas to the east, is used with reverence - each beam placed strategically.

The traditional architecture is a masterpiece of environmental intuition - a square embrace of stone walls orbiting a central hearth, its smoke curling through a single roof opening like a mountain spirit returning home. Four timber pillars stand as silent sentinels, their bases often linked by wooden ties that transform the structure into a living entity, one that sways with seismic tremors rather than resisting them [4]. Imbued in these native crafts are the skills of indigenous stone masons. Transcending a simple occupation, it is a cultural heirloom, passed down through generations like a sacred text. Despite the increasing use of concrete, these constructs persist though sparingly, and local artisans can be credited for much of this perseverance.

The arrival of paved roads and supply trucks, however, has instigated the spread of capital stylistic choices and modern principles. There exists a cruel irony in this “development.” The same roads that carry essential resources now deliver materials that undermine centuries of architectural intelligence. Official reports confirm what the Indigenous have always known: not a single traditionally constructed building collapsed during recent quakes, while their concrete counterparts crumbled. The indigenous technology - born of stone’s compressive strength and timber’s tensile grace - proved itself not just as cultural artifact but as superior science, evolved through generations of mountain dwellers listening to their environment. This showcases how the role of architecture goes beyond simply preserving memory of a time of peaceful coexistence, now rocked by the flurry of new and insensitive developments.

FROM RUINS TO RENEWAL:

RETHINKING RESILIENCE

Driven by realization, a quiet revolution is stirring in Hunza’s valleys. Centuries worth of wisdom is resurfacing, through the efforts of contemporary visionaries. The Altit Fort and Khaplu Palace, iconic artifacts of the locality, persist as prevalent and weathered remainders of indigenous construction. While contemporary structures around them rise and fall with the seasons, these ancient edifices remain unshaken, their Cator and Cribbage bones in tune with every seismic tremor.

A homecoming of these domestic construction techniques manifests in the walls of the Lief Larson Music School - a manifesto in mud and wood. Here, vernacular wisdom meets contemporary needs, Cator beams, sun-dried bricks and timber lattices dance to seismic whispers [5]. Crafted by local hands attuned to the land’s memory, the structure embodies a radical truth: development need not mean displacement.

This instigates a fleeting thought, how can architecture further serve the local populace, staying true to both the land and its people’s struggles? Where imported architectures shout their foreign grammar, how can a building converse in Hunza’s mother tongue - while functioning beyond its ability as a simple shelter.

THE THAWING HORIZON:

DESIGNING FOR AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

The answer lies in listening. To the farmers who chart irrigation channels by ancestral memory. To the elders whose oral epics hold codes of survival now fading like the art of Daastan Goi (Story Telling). This is a land where every stone whispers, if only we design with the patience to hear.

The discernment of these murmurs unveils a need for a sanctuary. A contextually responsive and spatially sensitive place to retreat for locals and visitors alike, when the earth rages unpredictably. With environmental and social sustainability of utmost significance, the retreat can facilitate many facets: a space for remembrance, a space for documentation, and a space for rehabilitation. All these aspects require protection to preserve the sanctity of culture, transfer it effectively and ensure livelihoods.

The previous observations culminate in the form of a community and facilitation center proposal – The Cultural Nexus. A place for revival and rehabilitation. This implementation materializes in reverence of a sacred geometry pulsing through Hunza’s bones. The rotating square of Ha, an ancestral fingerprint of local buildings, thus inspires much of the assembly. Surfacing in handicraft patterns, doorframe relief, and now this new living archive, whose geometry represents more than a pattern. It is cosmology in timber: Four beams are locking at right angles to cradle stories older than the Silk Road, their turns are cradling the sun’s shining rays to warm the hearth. The spatial program follows a sensitivity to land use, splitting the area into two zones: a space perpetuating cultural resilience; spaces for remembrance and documentation and a dedicated rehabilitation wing. These are separated by a naturally occurring grove of trees - a poetic and practical buffer acknowledging the cultural need for privacy amidst Hunza’s famed hospitality.

As a spiritual people, with a deep folklore and rich religious history, a center for cultural remembrance and discernment, and museum for its documentation emerges as an absolute necessity. The paradox of Hunza’s economy - tourists arriving seeking postcard-perfect vistas, careless in their voyage while the natives practice hospitability while preferring a degree of privacy – requires a response. The implementation of this realization is essential as Hunza’s heritage is a breathing culture that demands more than snapshots - it asks for witnesses.

This space unveils in the form of a construction techniques gallery built in indigenous methods and exhibited to reveal a chronology of development through built form. An exhibition of the arts and crafts of the region and its paintings complements the gallery, allowing for the sensory transmission of cultural legacy. A section built to facilitate, document, and preserve the natural wildlife and endangered species of the area is integrated into the proposal, respecting the close bond between nature and the cultural psyche. Additionally, an outdoor acclimatization zone is designed to host Daastan Goi performances and exhibitions of festivals, allowing for active cultural participation from both locals and tourists alike. The cultural acclimatization zone transforms with the seasons - a festival carousel by day, its rotating Ha-patterned sheds utilized as an acoustic cocoon at night when locals reclaim it for moonlit Daastaan Goi. The structure’s morphology allows it to adapt to both large-scale events and intimate storytelling sessions, ensuring continued use year-round.

The proposed Cultural Nexus thus reimagines tourism as a reciprocal ritual. The impartation stands secondary only to the propagation of indigenous building practices, fully exercised in this proposal. Rising from the valley floor like an echo of Altit Fort’s enduring wisdom, the adjacent rehabilitation center breathes with the ancient rhythms of Cator and Cribbage. Its low heighted silhouette - a single-story tapestry of timber beams - angles outward; each wall optimized to catch the first sun rays. Where the mountains block its path, recessed windows slice through thick masonry at precise 45-degree angles, carving daylight across rammed earthen floors.

Present within its walls, stone’s stoic strength marries timber’s flexible grace through Cator beams - horizontal wooden straps (50-120mm thick) that lace through masonry. Spaced at 0.3-to-1.3-meter intervals, these wooden ribbons transform rigid walls into dynamic systems, allowing structures to sway rather than shatter when the earth trembles [6].

The rehabilitation wing thus addresses the very real challenges of living in a region marked by seismic activity and environmental volatility. It includes flexible emergency shelters, clinic spaces, and storage for emergency resources - all built using the same indigenous techniques promoted throughout the proposal. This isn’t just symbolic - it’s a literal demonstration of resilience in practice, proving the strength of vernacular wisdom in contemporary crises. Here, every element honors the site, a place where culture and conservation intertwine. Walls rise not in defiance of nature but in dialogue with it.

Thus, Hunza’s Cultural Nexus is not merely a building - it is an embodiment. A breathing archive. A place where mud and memory intertwine. It invites the world not just to observe but to engage, to learn not just about Hunza but from it. And in doing so, it proposes a new kind of development - one that listens, responds, and endures.

CONCLUSION:

IF WINTER COMES, CAN SPRING BE FAR BEHIND?

Disaster and winter are mere turning points in the great plane of existence. Just as the Hunza valley has weathered countless avalanches only to bloom again, so, too, does true resilience lie in this perpetual return: not to some imagined past, but to the enduring wisdom woven into indigenous stone and timber. The designer’s task becomes that of a translator, teasing out from ancient tectonics of building the living syntax of survival - where “progress” is measured not in concrete’s rigid conquest of terrain, but in how structures breathe with their inhabitants’ rhythms.

Spring comes always as an intellectual awakening: when we stop asking what to build and instead ask who we are building for. The answer hums through every earthquake-resistant joint in Hunza reminding us that architecture’s highest purpose is to hold space for the stories, the seasons, and the sacred reciprocity between people and place.

This is the resurgence that matters: not the blind march forward, but the conscious spiral back to all we’ve carried wisely through time - a return that is not regression, but recognition. Recognition that the Cator beam, and the Cribbage technique are not remnants, but resilient frameworks for the future. In rethinking resilience, we do not abandon innovation; we root it in the fertile soil of memory.

This article was peer-reviewed by Martín Álvarez and Neha Fatima.

[1] AKDN: Focus Humanitarian Assistance (2010).

[2] Hayat et al. (2010).

[3] Sökefeld (2012).

[4] Hasan (1986).

[5] The WoW Architects (2021).

[6] Hughes (2000).

References

Ali, Wajahat, Traditional Construction Techniques of Gilgit-Baltistan and its Adoption for New Construction (Aga Khan Cultural Service Pakistan, 2010).

Cheema, Yasmin, ‘Towards an Inventory of Historic Buildings and Cultural Landscapes’, in Stephano Bianca (ed.), Karakoram: Hidden Treasures in the Northern Areas of Pakistan, 2nd ed. (Turin: Umberto Allemandi & Co., 2007).

Frembgen, Jürgen Wasim, ‘Traditional Art and Architecture in Hunza and Nager’, in Stephano Bianca (ed.), Karakoram: Hidden Treasures in the Northern Areas of Pakistan, 2nd ed. (Turin: Umberto Allemandi & Co., 2007).

Hasan, Arif, ‘The Indigenous Architecture of the Northern Areas’, extracted from an evaluation of the Self-Help School Building Programme of the Aga Khan Foundation for the Northern Areas (September 1986).

Hayat, Tahir; Khan, Imran; Shah, Hamid; Qureshi, Mohsin U.; Karamat, Sajjad & Towhata, Ikuo, ‘Attabad Landslide-Dam Disaster in Pakistan 2010’, ISSMGE Bulletin, vol. 4 no. 3 (2010) pp. 21-31.

Hughes, Richard, ‘Cator and Cribbage Construction of Northern Pakistan’, Aga Khan Cultural Services (January 2000).

Sökefeld, Martin, ‘The Attabad Landslide and the Politics of Disaster in Gojal, Gilgit-Baltistan’, in Luig, Ute (ed.), Negotiating Disasters: Politics, Representation, Meanings (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2012), pp. 176-204.

The WoW Architects, Hunza: Culture, Architecture, and Ruralscape in Pakistan’s Northern Region (The WoW Architects, 2021).

Online References

Aga Khan Development Network, ‘Music Curriculum Development Centres and Schools’, AKDN. https://the.akdn/en/how-we-work/our-agencies/aga-khan-trust-culture/aga-khan-music-programme/music-curriculum-development-centres-and-schools (accessed 12 April 2025).

AKDN, Focus Humanitarian Assistance Provides Relief to Landslide Victims in Hunza, Pakistan. https://the.akdn/en/resources-media/whats-new/news-release/focus-humanitarian-assistance-provides-relief-landslide-victims-hunza-pakistan (accessed 12 April 2025).

Lininger, Chris, ‘Hunza Valley Culture: People Born in the Mountains’, Epic Expeditions. https://epicexpeditions.co/blog/hunza-culture/ (accessed 12 April 2025).

Mir, Shabbir Ahmed, ‘Attabad Lake Swallows Shishkat’, The Express Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/16251/attabad-lake-swallows-shishkat (accessed 12 April 2025).

Rafi, Muhammad Masood; Lodi, Sarosh Hashmat; Kumar, Amit & Verjee, Firoz, ‘Seismic risk reduction in northern Pakistan’, Institution of Civil Engineers (2017). https://www.icevirtuallibrary.com/doi/10.1680/jmuen.16.00047 (accessed 20 April 2025).

Image Sources

Shuja, Ayza, Altit Fort Cator and Cribbage Construction (2024).

Google Earth, Attabad Lake in 2009, 2010, 2012, 2015, 2022, 36°20‘06“N 74°50‘53“E. https://www.google.com/earth/ (accessed 29 January 2026).

Areeba Shuja is a final year architecture student, based in Islamabad who is passionate about developing sustainable urban solutions. Her interests lie in green design and inclusive spaces, aiming to create thoughtful and practical architectural responses, while considering social and historical contexts.

B.Arch, School of Art, Design and Architecture, Islamabad, 2026

Published in Issue 2026

Will Spring be far?

Explore other articles in this issue: