Blooming

Beyond the Chaar Dewari[1]

Reimagining suburban Islamabad through gender, care, and space

by Jaisha Mubashir

Behind the chaar dewari, women sustain life through routines the city does not acknowledge. These four walls often become boundaries that isolate. Yet within them lies care, labor, and knowledge. This essay reimagines the chaar dewari not as a limit but as a beginning. Drawing from field research, feminist theory, and spatial analysis, it proposes a suburban framework that centers the everyday lives of women who sustain. It suggests responsive architecture through prioritizing the house as a site of labor, linking homes through shared spaces and creating an ecosystem at a macro level. Architecture that holds care at its core. Like the kachnar tree that blooms after a long winter, this is a season for return: a return to what we once knew, to spaces that connect, and to a city where women shape the landscape. A season of renewal. A reclamation of space and identity.

This article was peer-reviewed by Francisca Pimentel and Neha Fatima.

![[image 1]_.png](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/50ff09_927a2d7b785f46158454ad6aa1929a87~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_300,h_210,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/%5Bimage%201%5D_.png)

[Image 1] Site map with

Zone I marked in a soft red toward the northwest and

Zone V in a deeper red toward the southeast. The project site

is circled in yellow.

Image by the author (2025).

[Image 2] A visual sequence showing how the centrality of open space in domestic typology has changed (in the subcontinent) over time. Pre-Partition period (left), Transitional period (center) and Post-Partition period (right). Image by the author (2025).

[Image 3] A sectional study showing how key sites of domestic labor open into a central courtyard at the heart of the house. The drawing maps how daily activities like cooking, washing, and resting connect spatially.

Image by the author (2025).

[Image 4] Above: A hand-drawn illustration of a typical Pakistani kitchen, linked with attached spaces and micro sites of labor inside the domestic ecosystem. Image by the author (2025).

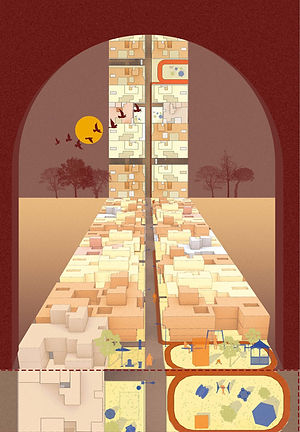

[Image 5] A collage illustrating the reimagined residential corridor offering two plot sizes and design options based on family structure and rental needs. Image by the author (2025).

[Image 6] Plug-ins at the macro scale that connect residential clusters through a central area by walking loops, activity nodes, and the participation of all genders and age groups.

Image by the author {2025}.

INTRODUCTION

This essay asks a simple question: How can the everyday patterns of homemaking women in Islamabad’s gated suburbs guide the design of more caring houses, streets, and neighborhoods? Everything that follows turns on that question. In Urdu, chaar dewari translates to “four walls,” symbolizing the rigid divide between public and private spheres, particularly for women. These walls, a legacy of British colonial rule, replaced South Asia’s domestic spatial logic [2], fractured community life, and rendered care work invisible, introducing instead the bungalow typology. [3]

Islamabad’s 1960s planners embraced this model to portray global progress. Even with mixed-use centers designed for a ‘human scale’ [4], Zone 1 (planned Islamabad) remains stubbornly car dependent. Meanwhile, Zone 5 (suburban expansion), was opened to private developers and it grows the fastest. It follows a North American suburban script: wide roads, gated plots, and detached houses oriented to the car.

The women at the centre of this study belong to middle-income families who live full-time within these schemes. Their stories, under the profiles of ‘Noreen’, ‘Ayesha’, ‘Sabiha’, are composites drawn from field interviews and survey responses collected during my 2024-25 architecture thesis at the School of Art, Design and Architecture, Islamabad. The project limits itself to domestic and near-home spaces, not addressing regional infrastructure or city-wide transit.

Building on feminist urban theory, field research (surveys, interviews, activity mapping, site sketching), and spatial analysis, the essay re-imagines the chaar dewari as a porous threshold rather than a hard divide. The three design scales that follow: The Chaar Dewari (house), The Chaaron Ghar (cluster), and The Chaaron Taraf (neighborhood). Like the kachnar tree [5], that flowers after a long winter, these interventions seek to nurture what can still grow.

CONTEXT AND BACKGROUND

A suburb built for the absent user

In the 1990s to signal national progress, Islamabad’s first suburbs inherited spaces rooted in the British bungalow model and North American suburbia. In Zone 5, more than three-quarters of households rely on a single breadwinner who commutes for work, while homemaking women manage and sustain the home. [6] Yet the street outside is built around the absent user. The spatial logic borrowed from contexts where women possess a different mobility access, falls apart in Pakistan. Here most homemakers rarely travel beyond a few hundred meters of the front gate. [7]

Sixty-feet inactive roads favor cars, and front setbacks push houses far apart. Even within neighborhoods, the isolation of the chaar dewari (house) ripples into meso and macro context. Boundary walls, locked gates, and parked cars dominate the street. While facades face one another, curtains stay drawn, and front lawns feel too exposed to be used.

What is missing is not just infrastructure; it is the chance for community. This erasure is also not accidental because the planning education still centers colonial ideas of the “ideal family,” while international guidelines sold as “neutral” continue to privilege the mobile, male commuter. [8] Until this lens changes, suburbs will continue to treat those who stay behind, mostly women, as an afterthought.

THEORETICAL FRAMING

No city is built in isolation; every bylaw, housing layout, and road dimension reflects the priorities of those in power. In a context like Pakistan, where labor divisions remain deeply gendered, this bias takes physical form.

Caroline Criado Perez reveals in “Invisible Women” how even global planning data excludes women’s bodies and routines. [9] Shilpa Phadke reminds us, that women’s very presence in public space is a political act [10] and Nourhan Bassam writes, that cities are built around patriarchal values that decide who moves, who lingers, and who belongs. [11] Together, their work shows how this kind of exclusion is not unique to Pakistan.

But care is not something that happens quietly in the background. It is skilled work. It takes time, energy, and presence. Bridget Anderson reminds us that domestic labor is not passive. When architecture fractures the routines of care, it adds exhaustion to already demanding lives. [12]

This essay does not just critique that fragmentation. It builds on existing practices of care to imagine what suburban space could become.

CASE ANALYSIS: THE ARCHITECTURE OF EXCLUSION

Historic domestic typologies:

the spatial logics of care

Before the widespread adoption of the bungalow, domestic architecture in South Asia followed an entirely different spatial logic. Houses were often organized around a central courtyard, with rooms arranged along the perimeter and connected by shaded verandahs. These courtyards were open to the sky but enclosed by walls, allowing airflow and privacy at once.

The architectural decisions behind this layout were both climatic and social. In regions where extended families lived together and caregiving was constant, the courtyard became a spatial hinge: kitchens, washing areas, storage zones, and even informal gathering spaces were placed in relation to it. Women could work, watch over children, interact with neighbors, and rest, all without moving across disjointed rooms. [13]

This shifted during British colonial rule. The introduction of formal drawing rooms, deeper setbacks, and compartmentalized floor plans reflected a move toward nuclear living and gendered spatial separation. [14]

Islamabad’s suburban housing (Zone 5):

a home that ignores its user

The prevailing house type in Zone 5 is a detached, front-facing unit with a car porch at the entry and an open space that is rarely used. Most follow developer-issued templates with no variation across plot size, orientation, or occupant needs. Without hiring a private architect, residents have little choice. The gated community’s design teams work without gender assessments, environmental audits, or any acknowledgement of caregiving as an architectural consideration. Tasks like cooking, laundry, supervising children, or assisting elders are secondary concerns. These homes are not just indifferent to women’s labor; they make it more taxing.

DESIGN INTERVENTIONS

A framework for spatial analysis

If the previous section showed how design has drifted away from supporting care, this one asks how we might bring it back. The following framework moves across three scales: the house, the cluster, and the neighbourhood. Each one responds to a specific spatial gap observed in the field, and together they build a housing model rooted in autonomy.

Micro level: The Chaar Dewari (Household)

Treating the home as a site of labor. Kitchens connected to courtyards, integrated laundry/play area, and ventilation-enhanced layouts.

Meso level: The Chaaron Ghar (Street + Cluster)

Cluster planning with communal courtyards, shaded walkways, and play areas.

Macro level: The Chaaron Taraf (Neighborhood)

Inclusive public spaces, accessible services, and mobility systems centered around non-driving users, especially women.

In the next section, these interventions are explored through the lens of three user profiles: ‘Noreen’, ‘Ayesha’, and ‘Sabiha’. These narratives keep the interventions from drifting into abstraction, allowing the designs to respond to actual patterns of care, constraint, and adaptation observed on the ground.

1. Micro level: the Chaar Dewari (household)

User Profile: ‘Noreen Ahmed,’ Age 37

‘Noreen’ lives in a 10-marla (~2700 sq ft) house. Her days are long and filled with movement. She wakes up before everyone, cooks, cleans, checks homework, folds laundry, and helps her mother-in-law move between rooms. Her kitchen faces a

car porch wall, with no cross-ventilation or natural light. The laundry is tucked in a dark corner and her child plays inside the bedroom.

By noon, she is already tired. Every task is located in a separate part: She carries wet clothes across the house, walks past the living room to reach the pantry, then returns to an overheated kitchen. The floor plan was not made with her in mind.

Reimagining ‘Noreen’s’ Day: A Responsive Chaar Dewari

But what if the house knew her?

Now, the house has a courtyard that the kitchen opens into and a window over the counter looks onto where her son draws. A small transitional space between the kitchen and the courtyard acts as part of the main circulation of the house. A breeze carries away the smell of tarka. [15]

She sits in the courtyard watching a myna [16] settle on the tree, while the milk boils in the kitchen. The floor tiles stay cool through the afternoon.

Clerestory windows vent steam while bringing in high light. The counter, stove, and sink follow a clockwise logic and storage is within reach. A narrow jaali [17] near the door filters street noise and lets her catch a glimpse of the push-cart fruit vendor without being seen. In the laundry room across the courtyard, she folds clothes in the summer breeze.

The house no longer fragments her labor. It anticipates it. It shortens it. It softens it.

2. Meso scale: the Chaaron Ghar

(Reimagining the cluster as a social spine)

User Profile: ‘Ayesha Rafiq,’ Age 26

‘Ayesha’ lives in a rental unit on the first floor of a house shared with her in-laws. Her entry stairs open into a narrow side corridor, and the terrace upstairs offers no privacy. She spends most of her day indoors caught between childcare and chores. She has lived in this neighborhood for over a year, but she rarely sees neighbors. Most evenings, Ayesha waits for her husband to return so they can walk to the park. Even though it is a long walk with the pram, it is worth the effort.

Reimagining ‘Ayesha’s’ Day: The Cluster of Care

Now imagine ‘Ayesha’s’ home as part of a residential cluster. Nine homes are arranged around a shared courtyard and narrow lane laid with interlock pavement that slows traffic and encourages pedestrian activity.

The communal courtyard has a tree and a bench under its shade where mothers sit while their children play. Each cluster contains a small commercial kiosk selling essentials such as milk, eggs, soap, phone credit. ‘Ayesha’ walks down with her daughter, who now knows the shopkeeper by name. The kiosk ensures safety even if the children are not accompanied by their caretakers.

Now the neighborhood’s women move between spaces that hold their presence. They know where to sit, where to stop, and where their children can run to.

3. Macro scale: the Chaaron Taraf

(A neighborhood that remembers care)

User Profile: ‘Sabiha Hashmi,’ Age 61

‘Sabiha’ spent thirty years as a schoolteacher. Now retired, she lives with her son’s family and cares for her young granddaughter. Her house is big but quiet. The street outside is too fast for her to cross, and there are no benches nearby. The only park in the sector is on the far side of the commercial zone, a fifteen-minute walk that feels impossible. She hasn’t stepped out with her granddaughter in weeks.

Reimagining ‘Sabiha’s’ Day: A Neighborhood That Belongs

Now, imagine a neighborhood designed around care instead of cars.

‘Sabiha’s’ house opens onto a street that is narrowed, planted at intervals, and stitched into a wider network of walkable links. A pedestrian loop connects her home to the neighborhood park, the market, and a civic corner. Along the route, shade trees mark resting points. There are benches where the elderly gather for story circles with their grandchildren. Nothing feels far.

The public library sits above the school overlooking a multilevel play area. The gym nearby has a jaali screened terrace, where ‘Sabiha’ enjoys her yoga classes while keeping an eye on her granddaughter playing in the park below. On Wednesdays she attends an embroidery circle, and on Sundays she walks through the women’s weekly bazaar. She buys spinach from a girl two houses away. The amphitheater hosts neighborhood shows, and the park is no longer empty. There is room for everyone.

The care that once rested only on her shoulders now spills onto the community.

CONCLUSION: A SEASON FOR RETURN

This essay began with a simple question: how do we design for those who remain? This isn’t a final proposal, but rather a beginning.

Looking at this development through the lens of homemakers like ‘Noreen’, ‘Ayesha’, and ‘Sabiha’, this project shifts architectural outcomes. Each scale of intervention offers actionable steps that can be adapted elsewhere.

To scale this approach, it must be taught and practiced. This means questioning who is designing and for whom. This project is one attempt at doing that. It means staying with this question in professional work, where real estate logic often overrides lived need. And it means pushing policy to respond to the daily geographies of those who stay behind to keep things going.

There is still space and time for a shift in direction through dedicated effort. The kachnar blooms for the patience of its roots in the winter, and the frost has lingered for long enough. Now it is the season for return.

[1] Translates to “four walls” literally, and a “dwelling” metaphorically.

[2] Alvi (2021).

[3] The bungalow originated in Bengal, suited to the humid climate and was adopted by the British for its resemblance to English cottages. But as it spread across South Asia, it became a symbol of status rather than suitability, displacing earlier courtyard-based typologies.

[4] Daechsel (2015), p.42.

[5] A native tree in Islamabad that bears pink flowers in spring.

[6] Research conducted by the author (2024).

[7] Adeel (2016).

[8] Perez (2019), p. 157.

[9] Perez (2019), p.20.

[10] Phadke (2011), p.97.

[11] Bassam (2023), p.6.

[12] Anderson (2000), p.1.

[13] Arshad (1988), p.28.

[14] Arshad (1988), p.26.

[15] Urdu word for tempering.

[16] starling.

[17] latticed screen.

This article is based on thesis work conducted in 2024-25 by supervision of Ar. Abdul Qayyum Khan with the Architectural Design Studio VIII at the School of Art, Design, and Architecture in Islamabad, Pakistan.

[Image 7] A reimagined masterplan transforming a previously typical North-American style suburban development into a care-centered neighborhood.

Image by the author (2025).

[Image 8] Urban section encompassing all three tiers of interventions.

Image by the author (2025).

References

Anderson, Bridget, Doing the dirty work?: The global politics of domestic labour (London: Zed Books, 2000).

Arshad, Shahnaz, Reassessing the role of tradition in architecture (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1988).

Bassam, Nourhan, The Gendered City: How cities keep failing women (n.p.: Independently published, 2023).

Criado Perez, Caroline, Invisible women: Exposing data bias in a world designed for men (New York: Abrams Press, 2019).

Daechsel, Markus, Islamabad and the politics of international development in Pakistan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Faiz, Zahida, Islamabad and automobile dependency: a consequence of modernist urban planning? (Ankara: Middle East Technical University, MSc thesis, 2023).

Hayden, Dolores, Redesigning the American dream: Gender, Housing, and Family Life (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002).

Interview between author and Ahmed, Noreen, (Islamabad, 15 November 2024).

Interview between author and Hashmi, Sabiha, (Islamabad, 21 December 2024).

Interview between author and Rafiq, Ayesha, (Islamabad, 13 December 2024).

Moatasim, Faiza, Making exceptions: politics of nonconforming spaces in the planned modern city of Islamabad (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, PhD dissertation, 2015).

Phadke, Shilpa, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade, Why loiter? Women and risk on Mumbai streets (New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2011).

Survey conducted by author with Zone 5 residents (Islamabad, October 2024 to January 2025).

Online References

Adeel, Muhammad, ‘Gender inequality in mobility and mode choice in Pakistan’, Transportation, vol. 44 no. 6 (2016), pp. 1-16. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/66726/ (accessed 9 April 2025).

Alvi, Yusra, ‘How British Colonial Architecture Excluded Pakistani Women from the Public Sphere’, Failed Architecture (2021). https://failedarchitecture.com/how-british-colonial-architecture-excluded-pakistani-women-from-the-public-sphere/ (accessed 16 April 2025).

Jaisha Mubashir is a recent graduate of architecture based in Islamabad. Her work explores the intersection of gender, space, and urban policy in South Asia. She is dedicated to playing a role in the global revolution of shaping cities that work for all.

B. Architecture, School of Art, Design, and Architecture, Islamabad, 2025

Founding Director, Shehr for Her, 2024

Communications Lead, APAD Research Group, since 2024

City Chapter Director Islamabad, FEM. DES. Network, since 2024

Published in Issue 2026

Will Spring be far?

Explore other articles in this issue: