The Architecture

of Reuse

Rethinking UK practice through Raymaekers and Sala Beckett

by Kleovoulos Aristarchou

This article investigates the role of material reuse in promoting sustainable architectural practice, focusing on the systemic challenges currently limiting its adoption within the United Kingdom. Despite increasing awareness of circular economy principles, the absence of supportive legislation, insufficient infrastructure, and restrictive certification systems continue to inhibit the widespread use of reclaimed materials. Through comparative analysis, the study examines two international case studies: Marcel Raymaekers’ salvage-based architecture in Belgium and the adaptive reuse of Sala Beckett by Flores and Prats in Barcelona. These examples illustrate distinct yet complementary approaches to reuse, one systemic and market-oriented, the other contextually sensitive and culturally grounded. Both demonstrate the environmental and ethical value of reusing existing materials in architecture. The article concludes that legislative reform, digital tools such as material passports, and institutional support are essential to embed reuse within the UK’s construction sector and to achieve a more sustainable architectural future.

[Image 1] Photograph of German Pavilion exhibition Open for Maintenance in Venice Biennale 2023.

Image by the author (2023).

[Image 2] Collage of 3 buildings designed by Marcel Raymaekers with reused elements.

Image/ Collage by the author (2025).

[Image 3] Photograph of Sala Beckett‘s Restaurant.

Image by the author (2024).

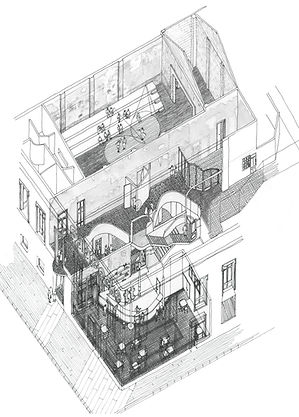

[Image 4] Hand Drawing of Sala Beckett. Hand drawing based on original drawing by Flores & Prats.

Image by the author (2025).

[Image 5] Photograph of Sala Beckett‘s Entrance Lobby.

Image by the author (2024).

[Image 6] Photograph of Sala Beckett‘s from the street.

Image by the author (2024).

INTRODUCTION

The built environment plays a significant role in the current scarcity crisis facing our planet, contributing to the depletion of finite resources such as fossil fuels and raw materials [1]. As the President of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) stated during a lecture at the Bartlett School of Architecture, by 2090 the global population is projected to reach 10.9 billion, an increase of 3 billion from today. To house this growing population, we must adopt creative approaches and prioritise the reuse of existing material resources [2] . This article examines the current state of reuse in architecture, the potential for its future development in the UK, and international examples that demonstrate innovative approaches to material reuse.

Several key questions are addressed: What are the current challenges facing the reuse of reclaimed materials in the UK? Does the architectural profession need to fundamentally rethink its approach to material resources? What exemplary projects exist?

The first part of the article examines the current state of reuse in the UK, outlining the systemic changes needed for a more ethically and environmentally sustainable future. It explores the pressing issues of construction waste, the environmental costs of demolition, and the UK government’s limited action in this area. Other barriers include the absence of adequate infrastructure for material reclamation and challenges related to the standardisation and specification of reused materials within current construction practices. Finally, the article calls for the establishment of organisations dedicated to resolving these systemic issues and supporting a circular economy in the built environment.

The second part of the article highlights two compelling international examples of upcycled architecture, due to the relative scarcity of notable projects within the UK. The first is the ad hoc salvage architecture of Marcel Raymaekers in Belgium. The second example is the transformation of the Sala Beckett in Barcelona, Spain.

The article aims to inspire the architectural profession to embrace the potential of reclaimed materials. The future of sustainable architecture lies in the reuse, repurposing, and rejuvenation of our existing built fabric. Now is the time to reorient the profession toward practices that are not only environmentally responsible but ethically sound. By doing so, we can contribute to a more sustainable way of living on the only home we have, Earth.

THE FUTURE IS IN RECLAIMED MATERIALS

The climate crisis compels humanity to adopt drastic measures to secure a sustainable future. A critical area for intervention is the construction industry, where the depletion of raw materials demands a fundamental rethinking of how we build. We must become more resourceful with the limited natural assets that Earth provides. Strategies such as carbon emissions reduction, renewable energy adoption, and the use of regenerative resources are essential, but equally important is the urgent need to embrace the reuse of building materials.

To ensure long-term sustainability, we must radically transform our current construction practices, enabling future generations to reuse the structures we build today. But how can this be achieved? How might government policy support the use of reclaimed materials? Are upcoming regulations sufficient to prevent reusable materials from ending up in landfills? How much can architects accomplish without government backing? Could tools like “material passports” facilitate the future reuse of building components? And what mechanisms can support the cataloguing and specification of materials for future reuse in construction?

According to a report by the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 66.2 million tonnes of excavation and demolition waste were generated in 2016 alone, accounting for 62% of the nation’s total waste that year [3]. A significant portion of this waste could have been reused in construction, potentially reducing demand for new materials and lowering carbon emissions.

The Architects Registration Board’s Competence Guidelines on Sustainability state that architects are responsible for applying circular economy principles across a project’s lifecycle. Yet, despite growing awareness and individual efforts, a large proportion of building components continue to be discarded rather than reused. Currently, no legislation mandates the reuse of materials from existing structures or demolition sites, an absence that significantly undermines waste reduction and carbon targets [4]. Nevertheless, some not-for-profit organisations, such as Material Cultures, ACAN, and Architects Declare, are working to promote alternative models for a more sustainable built environment.

The UK’s legal and contractual frameworks also discourage long-term thinking. Construction contracts typically protect building owners for only six to twelve years after project completion. Once this period ends, responsibility for maintenance and repair shifts entirely to the owner. This system incentivises short-term performance over durability and flexibility, discouraging the use of reclaimed materials and the design of buildings that can be easily repaired or adapted over time [5].

As a result, fewer high-quality materials are recovered from demolition sites, further limiting opportunities for reuse. To reverse this trend, we must fundamentally reconsider the materials we build with, and how we build with them. The short lifespan of many contemporary buildings, driven by the widespread use of synthetic petrochemical-based materials, poses another critical challenge. It is vital to consider the fate of building components at the end of a structure’s life. By integrating this foresight into the design process, we can significantly reduce waste and facilitate the reuse of materials [6].

At present, the UK lacks an infrastructure capable of systematically salvaging, storing, and redistributing reclaimed materials. By contrast, countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands have developed sophisticated systems that support a thriving market for reused building components.

While initiatives like Material Cultures provide important advocacy and research, systemic change must begin at the design stage. Recycling alone is insufficient. As Material Cultures argues, the entire approach to construction must be reimagined [7]. Even when clients and architects wish to incorporate reclaimed materials into their projects, they face logistical barriers, chief among them a lack of temporary storage solutions. Collecting sufficient materials from demolition sites is a time-intensive process, and without accessible storage, many potential reuse opportunities are lost.

Though limited in the UK, successful models exist elsewhere. One notable example is ROTOR DC, a Belgium-based organisation that specialises in dismantling, storing, and reselling reclaimed materials at scale. Such models offer valuable lessons for how the UK might build its own reuse infrastructure.

Compounding these challenges is the UK construction industry’s deep reliance on standardisation and data-driven certification systems [8]. Materials that fall outside these rigid frameworks, such as unique or non-standard reclaimed elements, are often excluded from specifications altogether [9], leading many architects to avoid them entirely.

To overcome this, dedicated organisations could assume responsibility for testing and certifying reclaimed materials, thereby transferring liability away from architects, clients, and contractors. This shift would help mainstream the use of reclaimed materials across the construction sector, reducing both environmental impact and resource extraction.

REUSE ARCHITECTURE: WHY AND HOW?

By 2030, we must reduce embodied carbon emissions by at least 50–70% [10]. Achieving this goal requires a radical rethinking of how we build. Increasingly, architects are embracing material reuse in creative and meaningful ways. However, they often face setbacks when clients opt to demolish existing buildings in favour of new construction. The absence of supportive legislation to restrict demolition and enable the reuse of building components undermines the architectural profession’s efforts to lower carbon emissions. Until such regulations are introduced, cultivating a robust culture of reuse in construction is essential.

To lay the groundwork for a more sustainable built environment in the UK, we must examine successful examples of salvage and repurposing strategies from elsewhere.

MARCEL RAYMAEKERS: THE REUSE PIONEER

A remarkable example of architectural salvage and material repurposing is the work of Marcel Raymaekers in Belgium. Raymaekers operated both as an architect and an antique dealer, selling reclaimed building elements. His home, Queen of the South, was surrounded by a yard filled with salvaged components sourced from architecturally significant sites, such as marble busts, carved stone fireplaces, columns, chandeliers, ornate doors, staircases, and other rare items. He also reclaimed more utilitarian materials such as bricks, marble, and wood [11].

From the 1970s through the early 2000s, Raymaekers personally visited demolition sites to salvage materials. He employed a dedicated team to collect, clean, and prepare these components for reuse, often assembling them into ready-to-install kits [12]. His core interest lay in preserving the embodied craftsmanship and geological history embedded in these materials [13].

Raymaekers’ architectural designs were almost entirely composed of reclaimed materials. His façades featured richly detailed elements, such as portal entrances, bay windows, iron railings, balconies, arches, and more [14]. Designing with salvaged elements required great flexibility; differences in size, quality, and condition meant that each project was shaped by the materials at hand. Rather than seeing this as a limitation, Raymaekers embraced it, allowing each unique component to fuel his creativity.

His pioneering work has influenced sustainable organisations such as ROTOR DC in Belgium and Material Index. These groups reclaim, clean, repair, and prepare building materials for reuse, often re-dimensioning or applying new surface treatments. Both organisations operate online platforms where designers and clients can browse and purchase salvaged elements. The architectural profession would benefit greatly from integrating these resources into regular practice.

SALA BECKETT: AN UPCYCLED MASTERPIECE

A more recent and compelling example of reuse in architecture is the Sala Beckett project in Barcelona by Catalan architects Flores & Prats [15]. Originally a workers’ cooperative named Pau i Justicia, the building has been repurposed into a theatre centre. At the outset, the architects spent three months carefully documenting the existing, abandoned building by measuring, drawing, and observing every detail [16]. This process not only deepened their understanding of the structure but also created a drawing inventory that guided construction and safeguarded it against the loss of original elements [17].

Since the building was unlisted, there was no legal obligation to preserve it. Nevertheless, the architects chose to retain and adapt it, driven by the cultural memory it held for the local community [18]. The project aimed to restore both the physical structure and its social significance.

Flores & Prats saw the existing walls and ceilings as bearers of emotion and memory (traces of past occupants that aligned with the client’s concept of storytelling). They valued existing decorations, such as tiles, rosettes, glasswork, doors, and mosaics for their cultural resonance [19].

After cataloguing all significant elements, some were stored temporarily, then reintroduced into new locations; others remained on site [20]. Only elements from the original construction were preserved, such as windows, doors, railings, tiles, handles, plaster details, and lighting fixtures [21]. The architects even recorded scars and imperfections in full detail to ensure careful handling by the builders. The reuse of existing materials not only lowered costs but also added richness and character [22]. With these materials, the building’s original culture returned.

Flores & Prats adopted a bricoleur mindset, as defined by Lévi-Strauss in The Savage Mind: someone who works creatively within the constraints of available resources, unlike the engineer who relies on purpose-built tools and materials [23]. The architects even moved into the building for a year, allowing them to gain deep insight into how best to transform it into a theatre, classrooms, and a restaurant [24]. Salvaged components were trimmed, adapted, or augmented to suit their new roles [25].

The sensitive reuse strategy employed in Sala Beckett echoes the radical reimaginings of Gordon Matta-Clark’s Anarchitecture artwork. Flores & Prats achieved an extraordinary reactivation of an abandoned building while retaining its memory, repurposing its materials, and minimising carbon emissions. With a modest budget and immense care, they created a culturally rich, low-impact building. Their work should serve as a model for UK architects aiming for sustainability and meaningful reuse.

Conclusion

Today, most building materials are recycled rather than reused. While recycling may seem environmentally responsible, it typically requires a high energy input, especially for materials like brick. Recycling avoids the labour-intensive processes of cleaning, restoring, and adapting components, making it more cost and time-efficient in the short term [26].

In contrast, material reuse is more labour-intensive and often more expensive, which discourages its adoption in the absence of policy support. To address this imbalance, new regulations must both enable the reuse of materials and reflect the true environmental cost of newly manufactured materials. If environmental impact were factored into pricing, reused materials would become more competitive. Furthermore, emerging technologies such as Building Information Modelling (BIM) offer promising tools to facilitate reuse. BIM can support the development of digital material banks and “material passports,” which record key information such as embodied carbon, origin, performance tolerances, and intended lifecycle [27]. Some countries already offer tax incentives for buildings that incorporate such passports [28]. The UK could adopt similar strategies to stimulate a more circular economy within its built environment.

The case studies of Marcel Raymaekers and Flores & Prats offer distinct yet complementary models of reuse in architecture. Flores & Prats present a site-specific strategy, creatively repositioning materials within the same building. Their decision not to demolish, but instead to embrace and reinterpret the building’s existing components, reflects a deeply ethical and regenerative approach. The architects used storytelling to justify retaining the existing building and had the full support of the client, even in the absence of legal frameworks. By preserving the urban memory embedded in walls, surfaces, and details, they minimise visual and cultural disruption. Their work has become a powerful source of inspiration for young architects, fostering a new wave of sustainable design thinking rooted in sensitivity and restraint.

In contrast, Marcel Raymaekers offers a systemic model for reuse across sites. His long-standing practice of reclaiming, cataloguing, and reintegrating architectural elements from demolition sites demonstrates how salvage can become the foundation of a viable and creative architectural language. His approach offers crucial lessons on how the integration of reclaimed materials can prompt a broader re-evaluation of construction practices and our material economy. Beyond aesthetics, Raymaekers’ method represents an expanded understanding of recycling, one that values not just materials but the embedded energy, craftsmanship, and history they carry. His approach bridges the gap between traditional salvage and contemporary ideas of circularity, showing that recycling need not reduce materials to raw inputs but can preserve their form, identity, and cultural value.

Together, these two practices underline the urgency and potential of reuse in confronting climate challenges. By learning from such precedents and pushing for systemic change (technological, legislative, and cultural), the UK can advance toward a genuinely sustainable and low-carbon built environment. The UK must establish a legal framework that actively supports the reuse of materials within the built environment. Introducing a legal framework to support material reuse in the UK’s built environment would reduce waste and carbon emissions, create economic opportunities, and promote sustainable construction practices. It would also help preserve cultural heritage and drive industry-wide innovation through clearer regulations and standards.

This article was peer-reviewed by Lavenya Parthasarathy

and Stefan Gruber.

[1] Lang, 2022.

[2] Kershaw and Oki, 2024.

[3] Wong, 2023, p. 236.

[4] Policy SI 7: Reducing Waste and Supporting the Circular Economy, and Policy SI 2: Minimising Greenhouse Gas Emissions are the only relevant policies in the UK, and they apply exclusively within the London area. It is worth noting that neither policy constitutes a legal framework, meaning clients are not legally required to comply with them.

[5] Dall and Material Cultures, 2024, p. 54.

[6] Dall and Material Cultures, 2024, p. 55.

[7] Dall and Material Cultures, 2024, p. 55.

[8] Dall and Material Cultures, 2024, p. 71.

[9] Dall and Material Cultures, 2024, p. 73.

[10] Foster, 2024.

[11] Capelle et al., 2024, p. 142.

[12] Capelle et al., 2024, p. 150.

[13] Ibid., 2024, p. 157.

[14] Ibid., 2024, p. 165.

[15] Flores & Prats, 2023, p. 44.

[16] Casares et al., 2018, p. 64.

[17] Ibid., 2018, p. 193.

[18] Flores & Prats, 2023, p. 46.

[19] Ibid., 2023, p. 46.

[20] Ibid., 2023, p. 66.

[21] Casares et al., 2018, p. 56.

[22] Flores & Prats, 2023, p. 66.

[23] Lévi-Strauss, 1966, pp.11–12.

[24] Casares et al., 2018, p. 82.

[25] Casares et al., 2018, pp.196–201.

[26] Capelle et al., 2024, p. 181.

[27] Capelle et al., 2024, p. 183.

[28] Wong, 2023, p. 237.

References

Adria, M,. et al., Thought by Hand: The Architecture of Flores & Prats, 3rd edition (Asia, China: Pacific Offset, 2022).

Architects CAN, Architects Climate Action Network (2024). https://www.architectscan.org/ (accessed 14 June 2024).

Architects Declare, UK Architects Declare Climate and Biodiversity Emergency (2024). https://www.architectsdeclare.com/ (accessed 14 June 2024).

Booth, E., ‘What forward-thinking architects are looking forward to is a circular future’, Architects’ Journal (2023). https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/opinion/what-forward-thinking-architects-are-looking-forward-to-is-a-circular-future (accessed 14 June 2024).

Brajkovic, S. M., How to Address Sustainability Holistically?: Avoid the Tunnel Vision on Carbon [online lecture] (2024). https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/mod/page/view.php?id=5959829 (accessed 04 June 2024).

Brookes, S., ‘How can unthinking demolition persist in net zero Britain?’, Architects’ Journal (2022).

https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/opinion/how-can-unthinking-demolition-persist-in-net-zero-britain (accessed 02 June 2024).

Capelle, V. A., et al., Ad Hoc Baroque: Marcel Raymaekers’ Salvage Architecture in Postwar Belgium, 2nd edition, (Ghent: Graphius, 2024).

Casares et al., Sala Beckett: International Drama Centre: Rehabilitation of the former Cooperative Pau i Justicia Poblenou, Barcelona, 1st edition, (Barcelona: Arquine, 2018).

Clark, G., RIBA Sustainable Outcomes Guide (London: RIBA, 2019).

Cobo, A., Maintenance, Ethics and the Profession [online lecture] (2024). https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/mod/page/view.php?id=5959844 (accessed 11 June 2024).

Dall, A. and Material Cultures, Material Reform: Building for a Post-Carbon Future (Italy: MACK, 2024).

Flores & Prats, Sala Beckett (2024). https://floresprats.com/archive/sala-beckett-project/ (accessed 07 June 2024).

Flores, R., and Prats, E., Flores & Prats: Drawing without Erasing and Other Essays (Slovenia: GPS, 2023).

Foster, I., Sustainability [online lecture] (2024). https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/mod/page/view.php?id=5959829 (accessed 04 June 2024).

Heilmeyer, F. , ‘Ad Hoc Baroque: The rediscovery of Marcel Raymaekers, pioneer of Belgian recycling’, Architects’ Journal (2024). https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/practice/culture/ad-hoc-baroque-the-rediscovery-of-marcel-raymaekers-pioneer-of-belgian-recycling (accessed 14 June 2024).

Kaminski, I., ‘Material Passports: finding value in rubble’, Architects’ Journal (2019). https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/material-passports-finding-value-in-rubble (accessed 02 June 2024).

Kendall, J., Ethics & Agency [online lecture] (2024). https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/mod/page/view.php?id=5959844 (accessed 11 June 2024).

Kershaw, A., and Oki, M., ARB and RIBA Lecture [lecture] (2024). https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/mod/page/view.php?id=5959819 (accessed 19 June 2024).

Lang, R., Building for Change: The Architecture of Creative Reuse, (Berlin: Gestalten,(2022).

Latour, B., Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018).

Lévi-Strauss, Claude, The Savage Mind / Claude Lévi-Strauss, Nature of Human Society Series. (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1966).

Material Cultures, Material Cultures (2024) https://materialcultures.org/ (accessed 14 June 2024).

Material Index, Material Index (2024). https://www.material-index.co.uk/index.html (accessed 14 June 2024).

Morgan, R, ‘Material Index’, lunch time CPD attended by the author (28 February 2024).

RIBA, RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge, (London: RIBA, 2019).

Rotor DC., Rotor DC: Deconstruction & Consulting (2024). https://rotordc.com/ (accessed 14 June 2024).

Vlaams Architectuurinstituut, Interview met architect Marcel Raymaeker: pioneer in circular architecture [Youtube] (2023). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NazfLkqQoGE&t=163s (accessed 14 June 2024).

Wong, L., Adaptive Reuse: Extending the Lives of Buildings, (Berlin: Birkhauser, 2017).

Wong, L., Adaptive Reuse in Architecture: A typological Index (Berlin: Birkhauser, 2023).

Young, L., et al, Machine Landscapes: Architecture of the Post-Anthropocene (Architectural Design) (Italy: Trento Srl, 2019).

Kleovoulos Aristarchou is practising architecture in the UK and Europe and specialises in projects with historic context. Kleovoulos is a design studio tutor at Sheffield School of Architecture and a guest critic and a mentor at The Bartlett School of Architecture. He talked at the London Festival of Architecture and various UK Universities. His interest lies in the materiality and craft of the city, as well as juxtapositions between historic and contemporary architecture, art, and theories.

Architect at Haworth Tompkins, London, UK

Design Studio Tutor at Sheffield School of Architecture, UK

ARB UK Architectural licence 2024

MA Architecture and Historic Urban Environments, The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL, 2021

MArch Architecture, The Glasgow School of Art, 2020

Published in Issue 2026

Will Spring be far?

Explore other articles in this issue: