Earthen Re[form]s

Low energy formworks for a convivial building process in rammed earth and adobe

by Rikunj Shah and Kaarel Kuusk

This paper highlights the potential of formwork as a tool to re-connect people with the building process in the context of rammed earth and adobe construction. Moving beyond purely technical concerns, it explores how the design of tools can facilitate collective participation, creativity, and joy in the act of building. Developed through an in-depth study of vernacular formworks, field experiments, and prototyping, the research presents three low-energy formwork concepts: the ‘rotational mould‘ for ergonomic adobe production, the ‘wave formwork‘ for modular non-orthogonal walls, and the ‘revolving mould-formwork‘ for versatile rammed earth units. Through these tools, a set of underlying principles for designing low-energy formworks that foster conviviality are articulated for further exploration and development. The research demonstrates that formwork is not merely a construction tool, but a social and cultural mediator in the practice of earth building.

![Earthenre[form]s_10.jpg](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/50ff09_4f4a4df2628347798b5182185765dc72~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_300,h_424,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/Earthenre%5Bform%5Ds_10.jpg)

[Image 1] Three prototype formwork tools tested during the prototyping phase, shown disassembled to reveal the individual components comprising each system.

Image by Kaarel Kuusk (2022).

[Image 2] Process sequence illustrating stages of the rammed earth construction of a small house in Nemesvámos, Hungary. The sequence shows the manual lifting of long corner formwork boards onto the plinth; laying and stomping of the cob mix to close air gaps; spreading of a wet straw–earth layer between successive lifts to improve interconnection and lateral resistance; and ramming by

community members. Image by the authors (2022).

[Image 3] Process sequence highlighting the adobe-making technique developed by local inventor Matudo Sabido in rural Brazil. The sequence shows the dumping of the earth mix into a forty-segment brick mould, its even distribution across all segments, the rotation of a lever handle to lift the mould using a

pulley mechanism, and the relocation of the assembly to begin the next production cycle.

Image by the authors (2022).

INTRODUCTION

Owing to its inherent cyclic nature and benefits to human health, earth as a construction material has re-emerged in the global quest of finding ‘viable’ alternatives for replacing steel and cement. This renaissance of earth-building is evident from the multiple trajectories that have emerged to ‘upscale’ the potential of this raw material so that it can meet modern building standards. Industrial offsite prefabrication of rammed earth panels [1] and in-situ robotical 3D printing with clay [2] represent the majority of these approaches where the communal and participatory aspects of the traditional earth-building process are overlooked for the pursuit of greater efficiency and productivity. This raises an important question: In our quest of upscaling earth, to what extent can the pursuit of efficiency dictate other aspects of the building process?

The scope of the present research is limited to examining formworks in the building processes of rammed earth and adobe construction, with particular attention to the emerging relationships between people, tools, and materials shaped through these practices. Conducted as part of the authors’ master’s thesis, the study integrates intuitive, first-hand construction site experiences of the authors with these two techniques and a review of secondary sources, including books and online materials such as on-site video recordings shared by builders around the world.

In rammed earth construction, a humid earth mix is compacted in layers within a formwork to create walls, while in adobe construction, a liquid earth mix is hand-thrown into moulds and later sun-dried to form bricks. Both techniques are labour-intensive and rely on communal participation. Historically, building with earth has always been a convivial process, rooted in collective effort and shared knowledge.

CONVIVIALITY IN EARTH BUILDING

Conviviality literally means jovial, festive, lively or cheerful. We use the term ‘conviviality’ in the same spirit as Illich does in his articulation of the term – something which is an opposing ideal to industrial productivity. In his book ‘Tools for Conviviality’, he argues for a need to rethink the idea of a ‘tool’ in an industrial society which is worth quoting at length:

“For a hundred years we have tried to make machines work for men and to school men for life in their service. Now it turns out that machines do not ‘work’ and that people cannot be schooled for a life at the service of machines. The hypothesis on which the experiment was built must now be discarded. The hypothesis was that machines can replace slaves. The evidence shows that, used for this purpose, machines enslave men. Neither a dictatorial proletariat nor a leisure mass can escape the dominion of constantly expanding industrial tools. The crisis can be solved only if we learn to invert the present deep structure of tools; if we give people tools that guarantee their right to work with high, independent efficiency, thus simultaneously eliminating the need for either slaves or masters and enhancing each person’s range of freedom. People need new tools to work with rather than tools that ‘work’ for them. They need technology to make the most of the energy and imagination each has, rather than more well-programmed energy slaves”[3]

Through centuries people across different cultures have always come together to build with this ancient material. With inherent benefits to human health, it allows people to be completely immersed in the building process with their mind, body and soul. Using simple tools like formworks, moulds and rammers, raw earth is slowly shaped into a building. Embedded with singing and dancing rituals, the act of building an earthen structure becomes a festive event in itself. The coming together of people with their hands and feet into raw earth, working with simple tools that allow for freedom and play, celebrating each step and creating heartfelt relationships along the way – this is the essence of the earth building process [Image 10].

LOW-ENERGY FORMWORKS FOR RAMMED EARTH AND ADOBE

Low energy formworks are the tools of the common people. People build these formworks by replicating, reiterating and reimagining the vernacular formwork to suit their contextual needs and preferences. What makes these tools ‘low-energy’ is that they are self-made with a highly frugal approach used in its making – formwork boards made out of locally available wood with simple and ingenious joinery with little or no use of industrial tools and methods. And precisely because of these low energy tools, a unique building process of building with earth comes about. Take for example the following documented cases for rammed earth. In the Hungarian village of Nemesvámos near lake Balaton, a unique iteration of the low energy formwork, built for a level instead of a block is seen [4]. Like the vernacular formwork, it is built by wooden boards and metal joints but instead of a block-sized formwork, the formwork is built in the same height as the block formworks for the entire wall area altogether [Image 2]. In western Bhutan, the tradition of rammed earth transcends mere construction activity and becomes almost like a performative art where people sing a specific song and dance to it together while building [5].

We can see even more innovation in formwork moulds when we look at contemporary adobe making processes. A local inventor Matudo Sabido from rural Brazil has developed a simple system for making forty adobe bricks in one cycle [6]. A forty-brick formwork mould is attached to a tarpaulin shed on wheels with a pulley system that allows for effortless lifting of the mould once the adobe mix is thrown and levelled inside the formwork [Image 3]. Another unique case of adobe block mould can be seen in the adobe making process in Kyrgyzstan, Central Asia. Combining the wheelbarrow, a table and the mould together, a new tool is derived which allows just one person to produce fifteen adobe blocks in one cycle [7].

These tools are not only reminiscent of the traditional way of building with rammed earth and adobe but show immense creativity in appropriating it to suit contextual needs whilst still being low-energy in its essence. The widespread use of such tools in remotest places where earth building is practiced even today is a testament to the flexibility and affordability it offers to the common people in how they desire to build their homes.

REINVENTING THE FORMAT OF LOW-ENERGY FORMWORKS

The format of ‘low energy’ tools ensures that the multiplicity and diversity of building processes of different cultures can continue to flourish in a global society. Building on this idea of the tool, three formwork concepts for rammed earth and adobe construction are proposed, each attempting to play with one specific parameter of the building process. These ideas reimagine the format of low-energy formworks to maintain not only convivial building processes but also maintaining a suitable level of efficiency.

'Rotational mould'

Making adobe bricks is a physically exhausting task. Most of the discomfort in the adobe building process arises from the non-ergonomic postures that people must maintain for prolonged periods. Additionally, producing a large number of bricks can be monotonous. This aspect of convenience - specifically related to human posture - is often neglected in adobe-making processes. [8]

The circular motion is the central principle in the design of the ‘rotational mould’, which encourages playfulness and provides comfort while throwing. The mould consists of four faces, each representing a different stage in the adobe production cycle [Image 4]. The adobes are extracted by turning over one of the bottom corners as the mould is relocated. This systematic motion creates an orderly arrangement of drying adobes. The tool features a comfortable 900 mm working height to ease workflow. The 90-degree hinge-like movement of the mould defines the shape of the chamfered adobes. The system allows the builder to choose between a regular and a lattice wall. A single mould enables a pair of people to work together simultaneously. [Image 5]

[1] Sauer, Kapfinger (2015), pp. 118-122.

[2] WASP (accessed 15 June 2023).

[3] Illich (1975). p. 23.

[4] Pintner (accessed 26 July 2023).

[5] Mandolicious Music

(accessed 23 July 2023).

[6] Sabido (accessed 26 August 2023).

[7] КАНЧА СОМ (accessed 28 April 2023).

[Image 4] Exploded axonometric view showing the components of the ‘rotational mould‘. Four mould segments, covered with a wooden board, are fixed onto a central metal frame using dowels.

Image by the authors (2022).

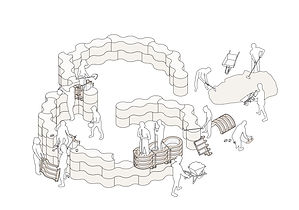

[Image 5] Illustration showing the adobe-making process facilitated by the ‘rotational mould‘. Two sets of moulds, each operated by two people, depict the sequential steps of filling, rotating, and extracting adobe blocks, supported by a worker cleaning the wooden board in a water tray to prepare for the next cycle.

Image by the authors (2022).

This article was peer-reviewed by Francisca Pimentel and Stefan Gruber.

'Wave formwork'

In rammed earth construction, every wall has a corresponding formwork used to build it. This limits the technique - primarily to straight walls - so that formworks can be reused multiple times. However, if one wishes to build a non-orthogonal wall using rammed earth, the formwork must be highly customised to the desired shape. Once customised, these formworks become redundant for use in other projects, making non-orthogonal rammed earth walls resource-intensive and expensive [9]. The greatest advantage of vernacular formworks lies in their modularity. The concept involves modifying the shape of the module to create a formwork that can extend in various directions. An equilateral triangle-shaped module allows replication on three sides, a square on four sides, and a hexagon on six sides. A circle - representing infinite possibilities - offers conceptual inspiration for the modules [Image 6]. These are proposed as formworks for producing non-orthogonal rammed earth walls. The resulting wall, made by combining the two modules, is structurally more stable than a straight wall and adds a sensual quality to the rough texture of rammed earth. It offers limitless possibilities for form, limited only by the modularity of the block and the imagination of the designer. [Image 7]

[Image 10] Members of the community dance in circles to mix earth, straw, and rice husk as part of preparing the adobe mixture at the construction site in Mae Sai, Thailand.

Image by Kaarel Kuusk (2022).

'Revolving mould-formwork'

Traditional rammed earth formworks have one major drawback: as the wall height increases, transporting raw material to the top, assembling the formwork, and ramming the earth become increasingly difficult. Without proper scaffolding, this can also be unsafe for the workers [10]. Traditionally, to overcome this challenge, rammed earth was used in conjunction with adobe bricks. Up to lintel height, walls were built using rammed earth, and above that, adobe bricks were used. However, adobe bricks typically have less compressive strength than rammed earth, making them less ideal at the critical junction where the roof structure meets the wall. Moreover, rammed earth is challenging to use for building walls within existing structures.

The ‘revolving mould-formwork’, as the name suggests, is a multifunctional tool that serves both as a mould and a formwork for producing modular rammed earth units [Image 8]. Designed for use by the common people in non-industrialised contexts, it provides flexibility and freedom in constructing rammed earth walls using a single tool. The design encourages a playful and communal in-situ fabrication process, allowing people to stay engaged with building [Image 1]. With this tool, a wide range of modular rammed earth units can be produced. Beyond reinventing the rammed earth building process and fine-tuning the vernacular formwork, the ‘revolving mould-formwork’ broadens the application of this ancient technique. With a single formwork, rammed earth can now be used in low-cost construction, refurbishments, and even interior applications within existing buildings.

THE CONVIVIAL ESSENCE OF LOW-ENERGY FORMWORKS

The ‘rotational mould’, the ‘wave formwork’, and the ‘revolving mould-formwork’ each explores different ways of rethinking tools for earthen construction and yet all of them are rooted in the principles of low-energy and conviviality. The learnings from these formwork studies can be distilled into five key parameters outlined below.

• Simplicity: The construction of an earth building is a long and tedious job. The formworks should entail simplicity in fabrication. They should be designed for intuitive use so that people from all walks of life are able to build it and use it themselves without the need for technical instruction or specialised training.

• Variability: The modern construction process is fragmented into narrowly defined repetitive tasks [11]. In contrast, the design of low-energy formworks should be flexible enough to have multiple possibilities of building with it. Rather than a predetermined method of operation, they should be open-ended allowing people to reinvent and adapt the formwork to better suit their contextual needs.

• Playfulness: When the building process is automated to the level of industrial precision, individual tasks become monotonous, leaving behind the creative and human dimensions of the process [12]. To counter this and keep people interested in the act of building, the low-energy formworks should be designed to spark curiosity and facilitate an inherent playfulness in use.

• Rhythm: In the conventional building process, the tempo with which people work is defined by the fixed tempo of industrial tools. The formworks should allow for people to choose a certain tempo of working which they feel comfortable with and in a way assist in synchronising different tempos of working of different people to create a rhythmic workflow, like in a choir or a live drama performance.

• Resourcefulness: Today, there is no consideration on the amount of energy that is expelled in the process of delivering the building of industrial quality and precision. The formworks should take a frugal approach with a focus not on using less resources but making the most out of energy and resources used in the process. They should demonstrate that it is possible to build a high-quality building while consuming the least energy and resources in the process.

This set of parameters can serve as a guiding framework inviting other earth building enthusiasts around the world to invent their own versions of low-energy tools for working with earth [Image 1]. The broader vision is not to over standardise the process, but to support the plurality of forms, rhythms, and cultures that earth building makes possible.

CONCLUSION

A common thread that emerges in the research is the deep-rooted and multifaceted relationship between people, tools, and raw materials in the building process. In the context of earth building, the tool is not just a means to an end - it is a connecting link between people and raw earth, and a bridge between tradition and modernity. The three formwork concepts explored in this research – the ‘rotational mould’, the ‘wave formwork’, and the ‘revolving mould-formwork’ - are not finished formwork kits. Rather, they are provocative tool concepts that remind us of the convivial essence of the earth-building process, which is equally, if not more, important than the apparent circularity of raw earth.

Due to time constraints, these prototypes, although designed as low-energy systems, are yet to be tested in real-life projects to ascertain their potential for enhancing convivial efficiency in the rammed earth and adobe building process. While these concepts can be readily adopted in non-industrialised contexts by owner-builders constructing their own homes, their application in industrialised environments such as cities will require further investigations and adaptation at scale. However, compared to industrial alternatives such as 3D printing and mass production – which largely isolate people from the building process - these formworks offer the possibility of leveraging local knowledge and indigenous wisdom, granting people greater agency in shaping their own built environment.By infusing fresh energy into the development of vernacular traditions, the project aspires to create a new trajectory for upscaling earth construction without being over-reliant on industrial methods. It invites a critical re-examination of the nature of tools and advocates for the design of building tools to be sensitive to the human condition – our physical capabilities, our social bonds, and our individual aspirations. Through the design of the low energy tools, the intention is to instigate a new building culture. A culture where the act of building is not outsourced but co-created. Where the tool does not replace the human but returns them to the centre of the building process. Where architecture is not a finished product, but a process of becoming – shaped by the people who inhabit it.

[8] Appian Media (accessed 12 May 2025).

[9] Yourhome (accessed 13 May 2025).

[Image 6] Exploded axonometric view showing the components of one module of the ‘wave formwork‘. Two curved sheet-metal sideboards, braced by a wooden structure and a wooden end piece, are held together using metal rods.

Image by the authors (2022).

[Image 7] Illustration demonstrating the system of interlocking rammed earth units forming a curved wall using

‘wave formwork‘ toolkit. Four formwork kits operate in coordination, enabling a systematic building process wherein one team constructs end units with alternating gaps, another fills these gaps, a third forms perpendicular branches, and the fourth offsets joints between successive lifts.

Image by the authors (2022).

[10] Shah (2023).

[Image 8] Exploded axonometric view showing the components of one arm of the ‘revolving mould-formwork‘. Two sideboards fixed to a central pivot rod rest on a wooden baseplate, with four brickforming segments separated by metal boxes, and the entire assembly secured with metal rods.

Image by the authors (2022).

[Image 9] Illustration showing the production of rammed earth bricks using the ‘revolving mould-formwork‘ system. Two teams of four operate the tool along a shared axis, one dismantling the formwork to extract bricks while the other compacts the mix. The boards are cleaned and rotated along the central pivot rods to reassemble the formwork in the opposite direction.

Image by the authors (2022).

[11] Nawi et al (2014). pp. 3-4.

[12] Chaplin (1936).

This article is based on a thesis project conducted in 2023 by supervision of Gian Franco with the Master of Advanced Studies in Architecture at BASEhabitat, University of Arts in Linz.

References

Sauer, Marko, ‘Prefabrication‘ , in Otto Kapfinger and Marko Sauer (eds.) Martin Rauch: refined earth: construction and design with rammed earth, (Munich, DETAIL, 2015). pp. 118-122.

no author, ‘3Dwasp‘, WASP. https://www.3dwasp.com/en/ (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

Illich, Ivan, Tools for Conviviality (William Collins Sons & Co Ltd Glasgow, 1975). p. 23.

Margaréta Pintner, ‘Kaláka-Part1:Building a rammed-earth structure the Hungarian way’, Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mBWd0kEs-jI5 (Accessed: 26 July 2023).

Mandolicious Music, ‘Rammed Earth Song and dance Bhutan’ , Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Q5Cs8uTUDE (Accessed: 23 July 2023)

Matudo Sabido, ‘Incrivel maquina de Faser tijolo caseiros’ , Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AyAwzKBeq8E (Accessed: 26 August 2023).

КАНЧА СОМ, ‘ОНОЙ ЖАНА ТЕЗ КИРПИЧ КУЯТУРГАН КАЛЫП’ Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aJPP7UZyehI (Accessed: 28 April 2023).

Appian Media, ‘Making Mudbricks like the Hebrews in Egypt - out of Egypt 5/12’ , Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9-XKoN_9R6I (Accessed: 12 May, 2025).

no author, ‘Rammed Earth‘ , Yourhome. https://www.yourhome.gov.au/materials/rammed-earth (Accessed: 13 May 2025)

Interview between Rikunj Shah and Margaréta Pintner (online, 2023).

Mohd Nawi, Mohd Nasrun, Nazim Baluch, and Ahmad Yusni Bahaudin. ‘Impact of Fragmentation Issue in Construction Industry: An Overview‘. MATEC Web of Conferences, 15 (2014) pp. 3-4. 10.1051/matecconf/20141501009 (Accessed: 11 May 2025)

Modern Times (United Artists, Charlie Chaplin, 1936).

Rikunj Shah is an architect working at the intersection of natural materials and contextual design. Deeply interested in indigenous knowledge systems of a place, he has contributed to multiple projects across diverse cultures and geographies. His work reflects an ongoing search for compassionate ways of designing and building spaces.

Founder, Studio Reverence, 2025

Master of Advanced Studies in Architecture - BASEhabitat, University of Arts, Linz, 2023

Diploma in Indian Aesthetics, Department of Philosophy, University of Mumbai, 2021

Registered Architect, Council of Architecture, India, 2020

Bachelor of Architecture, Bharati Vidyapeeth College of Architecture, Navi Mumbai, 2019

Kaarel Kuusk is an independent rammed earth construction specialist and a spatial designer fascinated by the architectural qualities and the symbolic richness of clay as a building material. In recent years he has contributed to the development of clay building culture at his home - Estonia and in the Baltics by mentoring earth building workshops and designing and building human scale rammed earth interventions.

Master of Advanced Studies in Architecture - BASEhabitat, University of Arts, Linz, 2023

Master of Arts (Interior Architecture), Estonian Academy of Arts, Tallinn, 2021

Bachelor of Arts (Interior Architecture), Estonian Academy of Arts, Tallinn, 2016

Published in Issue 2026

Will Spring be far?

Explore other articles in this issue: